The next time you fire up your copy of Photoshop, spare a thought for the scores of developers and the reams of code that have gone into making it…

While you won’t find it printed on any calendar, 2005 marks a quiet anniversary for the program that you, and many other graphic designers, probably use the most. It was 15 years ago in February that Adobe shipped version 1.0 of Photoshop – still its most popular (and lucrative) application, and possibly the only bit of software to have spawned its own verb form.

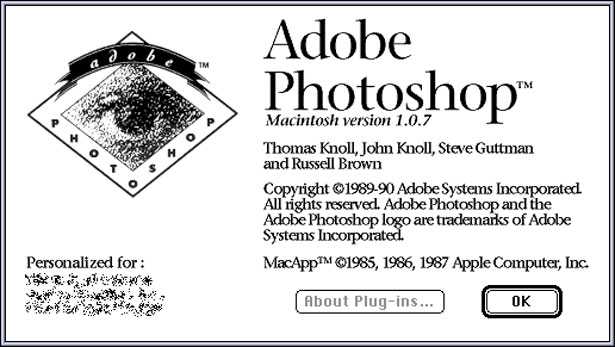

But the true origins of Photoshop go back even further. The program whose splash screen now displays 41 names was originally the product of just two brothers, Thomas and John Knoll, as fascinated by technology as they were by art. It was a trait they’d inherited from their father, a photography buff with his own personal darkroom in the basement and a penchant for early home computers.

Thus Thomas dabbled with photography, learning about colour correction and contrast in the darkroom, while John happily tinkered with his dad’s Apple II computer. When their dad – clearly an early adopter – bought one of the first Macs on the market in 1984, both were bowled over by its capabilities. Yet ironically it was its frustrating inadequacies that would eventually lead to the multi-million dollar application sitting on nearly everyone’s hard drive today.

In the beginning

By 1987, John Knoll was working at Industrial Light and Magic – Lucasfilm’s nascent special effects division, founded for Star Wars – while Thomas was studying for his Ph.D. on image processing at the University of Michigan. Having just bought a brand-new Apple Mac Plus to help out with his thesis, he was dismayed to find it couldn’t display greyscale images on the monochrome monitor. So, in true hacker style, he set about writing his own code to do the job.

Unsurprisingly, John was also working on image processing at ILM, and during a holiday visit he became very impressed with Thomas’s progress. In the book CG 101: A Computer Graphics Industry Reference, John says: “As Tom showed me his work, it struck me how similar it was to the image-processing tools on the Pixar [a custom computer used at ILM].” Thus the pair began to collaborate on a larger, more cohesive application, which they dubbed – excitingly – Display.

It wasn’t long before John had bought a new colour Macintosh II and persuaded Thomas to rewrite Display to work in colour. Indeed, the more John saw of Display, the more features he began to ask for: gamma correction, loading and saving other file formats, and so on.

Although this work distracted Thomas from his thesis, he was quite happy to oblige. He also developed an innovative method of selecting and affecting only certain parts of the image, as well as a set of image-processing routines – which would later become plug-ins. A feature for adjusting tones (Levels) also emerged, along with controls for balance, hue and saturation. These were the defining features of Photoshop, but at the time, it was almost unthinkable to see them anywhere outside of specialist processing software in a lab – or at ILM.

By 1988, Display had become ImagePro and was sufficiently advanced that John thought they might have a chance at selling it as a commercial application. Thomas was reluctant: he still hadn’t finished his thesis, and creating a full-blown app would take a lot of work. But once John had checked out the competition, of which there was very little, they realised ImagePro was way ahead of anything currently available.

From ImagePro to Photoshop

Thus the search began for investors. It didn’t help that Thomas kept changing the name of the software, only to find a name was already in use elsewhere. No one is quite sure where the name ‘Photoshop’ originally came from, but legend has it that it was suggested by a potential publisher during a demo, and just stuck. Incidentally, splash screens from very early versions show the name as ‘PhotoShop’ – which seems far more in line with today’s craze for ExTraneous CapitaliSation.

Remarkably in retrospect, most software companies turned their corporate noses up at Photoshop, or were already developing similar applications of their own. Only Adobe was prepared to take it on, but a suitable deal wasn’t forthcoming. Eventually, though, a scanner manufacturer called Barneyscan decided to bundle it with its scanners, and a small number of copies went out under the name Barneyscan XP.

Fortunately for the future of digital imaging, this wasn’t a long-term deal, and John soon returned to Adobe to drum up more interest. There he met Russell Brown, then Art Director, who was highly impressed with the program and persuaded the company to take it on. Whether through naivety on Adobe’s part or canniness on the brothers’, Photoshop was not sold wholesale but only licensed and distributed, with royalties still going to the Knolls.

It wasn’t as if this deal meant the Knoll brothers could sit back and relax; if anything, they now had to work even harder on getting Photoshop ready for an official, 1.0 version release. Thomas continued developing all the main application code, while John contributed plug-ins separately, to the dismay of some of the Adobe staff who viewed these as little more than gimmicks.

Curiously, this attitude still remains among some purists, who claim that most Photoshop plug-ins are somehow ‘cheating’ and not be touched under any circumstances, while others swear by their flexibility and power when used properly.

As in the program’s formative days, there were always new features to be added, and somehow Thomas had to make time to code them. With the encouragement of John, Russell Brown – soon to become Photoshop’s biggest evangelist – and other creatives at Adobe, the application slowly took shape. It was finally launched in February 1990.

Digital imaging for everyone

This first release was certainly a success, despite the usual slew of bugs. Like the Apple of today, Adobe’s key marketing decision was to present Photoshop as a mass-market, fairly simple tool for anyone to use – rather than most graphics software of the time, which was aimed at specialists.

With Photoshop, you could be achieving the same things on your home desktop Mac that were previously only possible with thousands of dollars of advanced equipment… at least, that was the implicit promise. There was also the matter of pricing. Letraset’s ColorStudio, which had launched shortly before, cost $1,995; Photoshop was less than $1,000.

With development of version 2.0 now underway, Adobe began to expand the coding staff. Mark Hamburg was taken on to add Bézier paths, while other new features included the Pen tool, Duotones, import and rasterisation of Illustrator files, plus, crucially, support for CMYK colour. This was another canny move on Adobe’s part, as it opened up the Photoshop market to print professionals for the first time. The program’s first Product Manager, Steven Guttman, started giving code names to beta versions, a practice which survives to this day. ‘Fast Eddy’ – version 2 – was launched the following year.

Until now Photoshop was still a Mac-only application, but its success warranted a version for the burgeoning Windows graphics market. Porting it was not a trivial task: a whole new team, headed by Bryan Lamkin, was brought in for the PC. Oddly, although there were other significant new features such as 16-bit file support, this iteration was shipped as version 2.5.

Like that difficult third album which can make or break a band, version 3 had to really deliver if it was to corner the market. Fortunately, the team had a whopper of an ace up their sleeve: layers.

By general consensus, the addition of layers has been the single most important aspect of Photoshop development, and probably the feature which finally persuaded many artists to try it. Yet the concept of layers wasn’t unique to Photoshop. HSC – later to become MetaCreations – was concurrently developing Live Picture, an image-editing app including just such a facility. While an excellent program in its own right, Live Picture was vastly overpriced on its launch, leaving Photoshop 3.0 for both Mac and Windows to clean up.

Nothing in later versions quite matched the layers feature for its impact, but there have nonetheless been significant changes. Version 5 introduced colour management and the History palette, with its extra ‘nonlinear history’ behaviour, which certainly opened up whole new creative possibilities. A major update, version 5.5, bundled Adobe’s package ImageReady in an entirely new iteration, giving Photoshop excellent Web-specific features. Layer styles and improved text handling popped up in version 6, and the Healing brush in version 7.

Today and tomorrow

Surprisingly given the age and market leading position of the application, Adobe continues to come up with new features for Photoshop. With Photoshop now part of the rebranded and remarketed Creative Suite 2, Adobe appears to be currently emphasising interoperability through the likes of Bridge.

But the program can’t and won’t stand still. For one thing, it faces much greater competition from a host of rivals, many of which claim to offer Photoshop’s power without the price. Lower-cost apps aimed at the amateur or home enthusiast, such as Paint Shop Pro on Windows, have had many years to learn from Photoshop. Adobe’s solution was to join them, launching the budget priced and feature-reduced but still immensely powerful Photoshop Elements – which itself has now reached version 4.

And the future? Unsurprisingly, Adobe isn’t telling. Photoshop is the jewel in its crown and its development is closely guarded. But there have been hints. Bryan Lamkin, now Senior Vice President of Digital Imaging and Digital Video, speculated earlier this year on a true 64-bit version of the application, and perhaps support for Apple’s CoreImage technology, which would bring enormous speed improvements. Rumours that Illustrator will merge with Photoshop have also abounded for years.

Whatever happens, it’s likely that Thomas Knoll will be involved in some way. Although not directly concerned with Photoshop these days, he still keeps his hand in, recently developing the Adobe Camera Raw plug-in and posting occasionally to the Adobe forums.

His brother still works at ILM too: appropriately enough, he was Visual Effects Supervisor on all three of the new Star Wars films. Without the original Star Wars, there would have been no Photoshop; and with no Photoshop, your job, this magazine and the entire graphics design industry would be very different from how they are today.